From the

Boston Globe:

Remains are identified as a boy pirate

He was a boy, no more than 11, when pirates captured the ship he and his mother were sailing on in the Caribbean. As he watched the pirates haul off the ship's cargo of sugar and tobacco, John King made a decision: He would leave his mother and join the pirate crew, led by Captain Sam Bellamy.

Now, 290 years later, King's remains -- his fibula, silk stocking, and shoe -- have been identified among the wreck of Bellamy's ship, the Whydah, 1,500 feet off the coast of Wellfleet. While teenage pirates were common in the 18th century, King is considered to be the youngest ever identified.

Researchers excavating the Whydah used 18th century Caribbean court records and modern forensics to make the determination.

Their find opened a window onto the strange and brief life of a young boy swept up in a lost world of ocean piracy.

``It's a whole touchstone to a period in history which is often misunderstood or it's been twisted around by all these novels," said Ken Kinkor, a historian at the Expedition Whydah Sea-Lab and Learning Center in Provincetown, which made the discovery. ``Even though we find treasures, the best treasures aren't always gold or silver. It's the knowledge we get from the past."

King's tale ranges through the Caribbean, to the coast of Venezuela, and finally to his watery grave off Wellfleet. It involves high-seas plundering, an appearance by the Puritan clergyman Cotton Mather, and a public hanging in Boston.

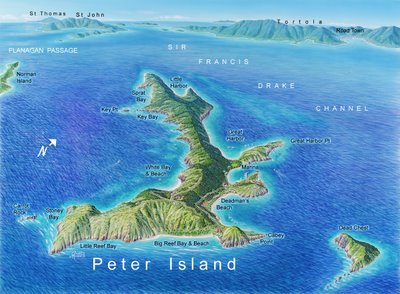

The boy's journey first entered the official records on Nov. 9, 1716. That is the date recorded in an Antiguan court deposition when Bellamy hoisted a black flag aboard his sloop, the Marianne, and attacked the Bonetta, the ship on which King and his mother were sailing, en route from Antigua to Jamaica.

The deposition, written by the commander of the Bonetta, tells how Bellamy plundered the boat for 15 days. The document also records a few of the 80 men on the Bonetta -- among them, a goldsmith named Paul Williams, a gunner's mate named William Osbourne, and an Indian boy and a black man, whose names were not recorded. Then the document, which Kinkor tracked down a few years ago in a London archive, tells of a boy, ``one John King," who stubbornly demanded to join Bellamy's crew.

King ``was so far from being forced or compelled" to join, the record says, ``that he declared he would kill himself if he was restrained, and even threatened his Mother, who was then on board as a passenger."

After the show of defiance, Bellamy let the boy aboard, Kinkor said. The moment has tantalized pirate enthusiasts for some time, who have struggled to understand why a pirate captain would let a boy join his crew.

``I tend to think that from what we know of Bellamy he was kind of a charismatic individual," Kinkor said. ``I think Bellamy may have admired the kid's spirit. This kid, I can almost see him begging Bellamy to let him join and Bellamy not having the heart to refuse."

Three months later, Bellamy and the boy would be dead.

From St. Croix, they sailed through the Leeward Islands, passed Venezuela, and crossed back toward America, plundering ships along the way, according to Kinkor. Between Cuba and Haiti, they attacked the Whydah, a 100-foot heavily armed slave galley, and Bellamy took the boat for his own. Up the Carolinas they sailed to Cape Cod, where a fierce storm sank the Whydah, killing roughly 140 men aboard, including Bellamy and King.

Thoreau reflected on the famous shipwreck in his book, ``Cape Cod".

``A storm coming on, their whole fleet was wrecked, and more than a hundred dead bodies lay along the shore," he wrote, referring to Marconi Beach in Wellfleet.

Six who survived were hung for piracy in Boston; two were acquitted with the help of Cotton Mather. An Indian survivor was sold into slavery, Kinkor said.

The boat, broken to bits, lay on the sea floor until 1984, when Barry Clifford, a Cape Cod native captivated by the tale as a boy, located the wreck using sonar. Clifford hauled up some 200,000 artifacts -- pistols, coins, and cannons -- and helped create the Whydah Center to display them. He hardly paid attention to King's fibula, stocking and shoe, found preserved in a lump of minerals in 1989 and put away in storage for years.

Clifford said he thought they belonged to a very small sailor, until Kinkor persuaded him recently to have them tested. ``I had been looking at this shoe and thinking, 'My God, these people were small back then," Clifford said.

Last month, John de Bry, director of the Center for Historical Archaeology in Florida, and David R. Hunt, an anthropologist at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C., analyzed photographs of the 11-inch bone and determined that it belonged not to a small man, but to a boy between 8 and 11 years old. Because King was the only boy recorded aboard the Whydah, Kinkor said he feels certain that the fibula is King's.

Although the English Navy used boys as ``powder monkeys" to haul gunpowder from the magazine to the cannons, Kinkor said he did not know of any records of a pirate so young as King.

The Whydah Center, which has the bone, stocking and shoe on display in Provincetown, plans to put them on a cross-country tour with National Geographic later this year, Clifford said.

A drawing of the Whyda, the pirate ship that John King is believed to have been sailing on when he died. (Expedition Whydah Sea-Lab & Learning Center)

A drawing of the Whyda, the pirate ship that John King is believed to have been sailing on when he died. (Expedition Whydah Sea-Lab & Learning Center) The silk stocking, shoe and fibula believed to be John King's, found in the wreckage off Wellfleet. (Expedition Whydah Sea-Lab & Learning Center)

The silk stocking, shoe and fibula believed to be John King's, found in the wreckage off Wellfleet. (Expedition Whydah Sea-Lab & Learning Center)